Hey all! So every once in a while, we’re not going to talk about pedals. We’re going to have a geek out blog post about music. Yes, that thing that we are actually supposed to be making with all the musical equipment that we buy! Why would we even talk about this? Well, simply put, it’s essential to think about what goes into making rock and roll fun. Plus, it’s a nice way for us both to waste some time. Read on – it’s going to be fun, and you’ll see I’m not afraid to reveal myself as a real ’80s guitar nerd.

Hey all! So every once in a while, we’re not going to talk about pedals. We’re going to have a geek out blog post about music. Yes, that thing that we are actually supposed to be making with all the musical equipment that we buy! Why would we even talk about this? Well, simply put, it’s essential to think about what goes into making rock and roll fun. Plus, it’s a nice way for us both to waste some time. Read on – it’s going to be fun, and you’ll see I’m not afraid to reveal myself as a real ’80s guitar nerd.

So I recently had an interesting conversation with a fellow guitar player about playing covers, and specifically how much of a well known song’s guitar solo should be played note-for-note. There are certain things that audiences often expect when they hear a tune, and certain guitar solos can be particularly melodic and memorable. In many instances, there can be turns of phrase on the instrument as memorable as any specific, compelling lyric from the lead singer, and an essential part of what we consider “the song.”

On the other hand, many of the greatest guitar solos we can think of were basically improvised, off-the-cuff streams of consciousness applied to the fretboard. The players themselves don’t think of their own work as sacred; even classic solos such as this one or this one can be changed, altered, or expanded upon in a live setting. If the artists themselves feels at liberty to change and revise these classic moments, how loyal should us mortals be?

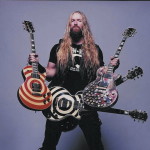

This is where the particular wisdom of Zakk Wylde can be really useful. As a vital part of the exclusive brotherhood of Ozzy Osbourne’s guitar slingers, Zakk spent much of three decades responsible not only for his own bone-crunching riffs and skyward solo bends, but also for maintaining a legacy of some true guitar hall-of-fame legends: Tony Iommi (the founder of Black Sabbath and Godfather Corleone of heavy riffage), and the late Randy Rhoads (a man whose import to guitar geeks approaches something like Roger Staubach’s importance to Dallas Cowboy fans).

*Lest you not want to grant us this much latitude in comparing Ozzy fans’ passion for their guitarists to Cowboys fans feelings for their quarterbacks, there are parallels. Rhoads’s fleet fingered scalar and modal runs from Blizzard of Ozz or Diary of a Madman are the Staubach jump passes and mad scrambles of their respective fans’ nostalgic highlight reels, while his revered classical guitar training was as much a testament to formality and discipline as Staubach’s Navy background and service. When Zakk Wylde arrived in the late 1980s, the Ozzies finally received the Aikman they had been waiting for – a forceful, accurate, and freakishly strong armed corn-fed Southerner (via Bayonne, New Jersey or UCLA) with the kind of sonic heft, velocity and drive that helped Ozzy thrive even during the grunge heavy early 1990s. The long blond hair, white Les Pauls, and stage mannerisms also couldn’t hurt with endearing the young Wylde to the faithful eager for an heir to their tragically departed champion.

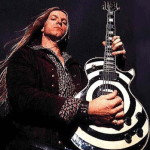

But in between these two eras, the criminally under-appreciated Jake E. Lee held the gig for Ozzy from 1983 to 1987. After besting future guitar god, kamikaze fetishist and online guitar instruction impresario George Lynch (Dokken, Lynch Mob) for The Gig, the man born as Jakey Lou Williams wrote and performed on two smash albums that went platinum despite overuse of ’80s production techniques, only to be reportedly fired via telegram(!) by Ozzy’s wife and future daytime talk show host Sharon while working on a muscle car. [If that isn’t a rock and roll story worthy of a Drive-By Truckers song, I don’t know what is.] Let’s examine one of his finer contributions, the live performance of the title track from Ozzy’s Bark at the Moon, featuring one of the most ostentatious drummer placements ever on a live set, and solos starting at 1:52 and 3:31.

But in between these two eras, the criminally under-appreciated Jake E. Lee held the gig for Ozzy from 1983 to 1987. After besting future guitar god, kamikaze fetishist and online guitar instruction impresario George Lynch (Dokken, Lynch Mob) for The Gig, the man born as Jakey Lou Williams wrote and performed on two smash albums that went platinum despite overuse of ’80s production techniques, only to be reportedly fired via telegram(!) by Ozzy’s wife and future daytime talk show host Sharon while working on a muscle car. [If that isn’t a rock and roll story worthy of a Drive-By Truckers song, I don’t know what is.] Let’s examine one of his finer contributions, the live performance of the title track from Ozzy’s Bark at the Moon, featuring one of the most ostentatious drummer placements ever on a live set, and solos starting at 1:52 and 3:31.

I was really surprised to remember a magazine interview from a long time ago where Zakk Wylde mentioned how covering the Jake E. Lee penned tunes could be tougher for him than playing the Randy Rhoads tunes. At the time this comment seemed strange to me, considering the massive gulf in perception between the players, but upon years of examination and reflection on their respective playing styles, it makes a lot of sense. Jake E. Lee has a right hand pick attack that is pretty much unlike anything else in 80s/90s rock. It might not be the fastest or most precise, but it may be the best *sounding*, rivaled among his peers perhaps only by (current Rihanna sideman!) Nuno Bettencourt’s. While not classically trained, Lee worked up his chops listening to and learning passages from serious fusion pioneers like John McLaughlin and Al DiMeola, rotating them in with the fundamental Page/Beck/Hendrix diet of rock players coming of age in the 1970s. With an attack this clear and punchy, he easily alternates between eighth note triplets and sixteenth notes, and punctuates his lead bursts with tight, tense slingshot vibrato. Bringing all that very fast and hard picking through a very raw tone – a Charvel modded superstrat loaded with a passive Duncan humbucker with a Boss OD-1 overdriver and ’70s Marshall amplifiers – Lee has pick strokes that can sound like a tommy gun emptying an endless magazine of shells at a bank vault door. By genre and role, Zakk and Jake should be pretty similar players, but on a host of technical and stylistic issues, they couldn’t play much more differently.

When asked how he would play the Lee songs, I recall Wylde gave an answer that I think is particularly instructive to musicians tasked to faithfully play a cover. He said something along the lines of playing the lead and rhythm parts with the right spirit, the right respect, and something along the lines of how he’d imagine Jake E. Lee would have wanted Zakk to play them. With that in mind, here is his take on “Bark at the Moon”, with lead breaks at 2:05 and 3:49:

Here you can see Zakk has made adjustments that suit his playing style, but he remains loyal in spirit and composition to what Jake wrote and created. Zakk’s Gibson Les Paul & active EMG-81 pickup tone is thicker and creamier, the band has downtuned and slowed the tempo to give Ozzy’s aging vocal range a fighting chance, and his particular gifts (furious left hand legato, a broad vibrato, absolutely massive sound, and those horse-whinny low E pinch harmonics!) are in ample evidence.

He’s never going to sound *exactly* like Jake, even though at the time of this recording, Zakk may have played Jake E. Lee’s “Bark at the Moon” parts thousands of times more than Jake ever had the opportunity to. Between who Zakk Wylde is as a player, his tone, his gear, his hands, his mind, his training, and his abilities, he’s never going to have that *exact* train-smashed-coin-meets-music-box pick attack across his guitar strings. But he sounds fantastic, and for all intents and purposes it all sounds, and more importantly, feels, like “Bark at the Moon”: the locomotive sixteenth note A minor riff, ascending triplet scalar runs that generate the tension through the end of the guitar solo, the outro arpeggios fit for a horror soundtrack. The media and the masses may sometimes treat Jake E. Lee like Ozzy’s beleaguered Danny White, but for all his bluster and bloozy public persona, Zakk Wylde shows him massive, genuine respect through the way he plays those parts. While in the end our choices as players totally depend upon the setting, audience, and our personal intentions, those of us who get asked to play covers could do well by following his example.